Paths to Internationalization: Challenges and Opportunities

Questions and notes about “thinking international” as Brazilian academics

On the 17th September, I had the honour to take part in this year’s inauguration lecture of the “Universidade Federal Rural do Rio de Janeiro’s” History Course. The date also marked the launch of the History’s Department YouTube Channel (“Humanidades na Pista”)

In the event, there were reflections about what the Brazilian university student can use as ways and strategies to reach their internationalization. We also discussed the UK’s case as a internationalized country, regarding its Higher Education sector.

In this article, you will find the notes to our talk, links to all websites mentioned, and a list of complementary readings for the subjects we discussed.

Watch the webinar video HERE

Initial thoughts and a little about me:

Although we are living through a critical moment in the world, the discussion about university internationalization is relevant. Some analysts think the crisis will represent the end of face-to-face learning and academic mobility. Yet, history has shown us that wars, crisis periods and epidemics have not stopped the phenomenon of students and scholars leaving their homes on a quest for education and knowledge. Besides, the current crisis period can point to more scientific collaboration between researchers and research centres – as collaboration is vital for the development of education, knowledge and the search of solutions to problems in common.

United Kingdom Higher Education is synonymous with internationalization. Despite not being a huge country (with a territorial extension equivalent to the State of São Paulo) and around 66,5 million inhabitants, remarkably, 4 British universities ranks among the ten best universities in the world.

For a Brazilian student, internationalization seems to be a distant dream, an almost impossible task, considering the current social and economic scenario in Brazil. But we believe you can achieve it with the right strategies, making use of all available technological resources, and personal investment in time, studies and work to reach your goals.

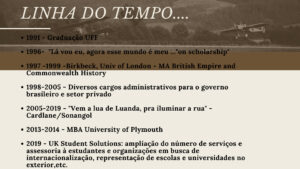

Question N.1: How was your start? How did you get to the UK?

- After my graduation in History (UFF -Brazil), I worked as a teacher for a few years; I also worked as a secretary. A friend of mine (today, Dr Ana Emiliano, a researcher at the University of Columbia, NY) told me about a scholarship scheme in London, for language studies. She had just returned from the UK where she had studied for one year.

- I applied for the scholarship; the school offering the scholarship accepted me, and I came to the UK. The programme was for a six-month English programme.

- The scholarship ended, but I stayed and explored all possibilities of starting a Master’s degree – academically and financially. I worked, and after English exams, application and further interviewing, Birkbeck, University of London accepted me as a student. My chosen programme was a challenge because I faced a somewhat different pedagogical method. There were no Pre-Masters programmes at the time (Pre-Masters studies enable overseas students to adjust better to the British educational way). The course focused on a new subject to me: British Empire and Decolonisation in the 20th Century. My interest in African Studies attracted me to the programme. Although I was not fluent in the academic vocabulary and jargon, I trusted in my instincts and my training and went for it.

- It was a challenge to adapt to the objectivity and conciseness of the English language, the rules for written work and presentations, and the intensity of the course. There are word- caps on essays, exams and in the dissertation. Students develop their academic work independently most of the time. There is an extensive amount of reading and writing; however, students spend less time in the classroom compared to a Masters programme in Brazil.

- The British educational model demands focus and organisation. Full-time Masters courses in the UK typically last for one academic year. I attended it on a part-time basis because I had Italian citizenship and was working full time to support my studies.

- I experienced the benefits of the British educational system: the institution’s infrastructure and facilities such as 24/7 open workstations, libraries available from 8 a.m. to 11 p.m. (including Saturdays, Sundays and Bank Holidays), the opportunity to request books from all universities in the UK, the access to all London universities and museums archives, the History Department and the Student Union’s vital support services and the teachers’ encouragement. I had free tuition to overcome the academic difficulties I faced when adapting to the new exams and written work model. All those factors were invaluable for my approval and successful course conclusion.

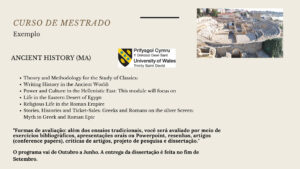

Example of a History Masters Syllabus

Question N.2: What is the profile of the student who wants internationalization?

The current Brazilian government has been imposing difficulties and obstacles for the funding of students, scholarships, research, and programmes of academic collaboration. Nonetheless, Brazilian students must aim for more.

We are living through a troubling period when no value is given to the academy, and the public is misinformed about science and knowledge – this is, unfortunately, promoted by the current Brazilian educational authorities – they cannot connect the nation’s development to a public policy of education.

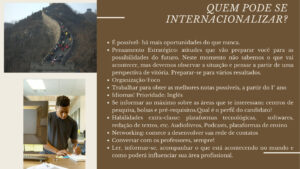

However, the 21st-century student must seek for viable and existing ways and persist towards their internationalization. There are plenty of opportunities available in international organizations, governmental, non-governmental, and even in the private sector. Internationalization in Higher Education increased the number of scholarships and options for academic collaboration. It has also made the application process for sponsoring and funding easier for scholars and students. Yet, to achieve this goal, we suggest the use of some tactics:

- Development of strategic thinking: a strategy involves attitudes that l prepare for the possibilities of the future. My approach, though I could not afford to travel or study abroad, was: working on my English skills, keeping an open mind to opportunities available, applying for the Italian passport I had a right to, and focusing on the European options to further my History studies.

- A strategist observes the situation and thinks from a victory’s perspective. We do not know what is going to happen tomorrow or what is going to be the result, but we must prepare for several outcomes, even if we need to retreat! A strategy is a capacity to think about the future, and if the sooner I prepare for it, the better my strategy will be.

- Aim for the top of your class at university, from the beginning of your course. Outstanding results will be significant in any scholarship application, not mentioning they will increase your confidence in your ability.

- Start thinking about the English language as a working tool. This skill will enable you to reach academic work produced worldwide, and academics and institutions. Work to gain an excellent understanding of the language. If you cannot afford to attend an English course, use resources available to you: apps, online exercising – there are several tools available to language learners today. Remember, 15 minutes on a language app daily means 15 minutes closer to your study abroad dream.

- Figure out which historical field or fields you want to pursue. Once you decide, look into existing research centres and scholarships available in your favourite study area.

- Always stay up-to-date with the world’s current events. Monitor the opportunities that can result from those events. For example, the African Union’s Agenda Africa 2063 is a project to be followed by those interested in African studies, as educational projects will be part of this Agenda.

- Go in pursuit of extracurricular knowledge: have a go at new technologies, learning a second and maybe a third language; why not improve your writing or learning to work on a new database software? In 2002, when I pursued a Local History Diploma course from Oxford University, I had to work on online learning platforms (they were a novelty at the time). I also used Microsoft Office’s Excel and Access programmes to build up databases from original documents provided by the university (wills, parish registers, letters, etc.) My previous knowledge of “Office” tools was critical and enabled me to complete the course. The study of history is a dynamic process, and the ability to extend yourself and research independently into your interests is an invaluable skill. Universities and scholarship providers expect more than just subject knowledge. Engaging in academic and broader enrichment tasks show your interest in moving beyond school programmes as an up-to-date modern historian.

- Start developing your professional network. Make social networking work for you and your project – instead of following pointless information on the net. Search for professional groups, follow the pages of organizations of your interest, watch videos and debates promoted by important historians and thinkers. You will always be up-to-date with new publishings, research and historiography. Update your LinkedIn page: do not assume it is only a job search tool. LinkedIn is a world professional network – you can connect to students and academics, follow universities, take part in debates, read and publish your articles and learn about scholarships. The possibilities are endless. Register on Academia.edu, where you will post your academic work, read other peoples’ researches, get in touch with them and exchange ideas with other professionals interested in the same research fields you are.

- Organisation and Focus: Spare one hour a day, one hour per week or some hours per week, according to your availability, to work on your internationalization and your extracurricular learning. When you think it is too hard, ask yourself: should I spend one entire hour randomly surfing on social media – knowing that this will not add any value to my life? Or should I use this hour focusing on something that will help me achieve my dreams of studying abroad? Time is a costly and rare commodity, use it to invest in you! The less time we waste with useless things, the better strategists we become.

- Build your life’s cultural project: read outstanding books, watch movies, listen to music, go to museums -shortlist what adds value to you. Building up knowledge and cultural intelligence will be important in your professional life, whether in your country or abroad. There are excellent strategies to achieve that: listening to podcasts, audiobooks, downloading classic literary works that are available online, watching YouTube’s academic review channels – there are thousands of options. Prepare yourself culturally for a life abroad. In my time, we would depend on physical books, records, DVDs. Nowadays, access to culture and art is cheaper and available.

- Talk to your teachers: Listen from who experienced the same challenges. Exchange ideas, ask for suggestions.

- Find your purpose: What do you want for yourself as a professional? Knowing what you want will be very important for the scholarship applications you are going to submit. Universities and organizations’ assessors will ask you about your motivation and your life goals after the course or training you intend to embark on. Not mentioning this is essential for your planning and the choosing of your strategies.

Real strategists cannot stop thinking about education. We are long-life students – not only graduates, but a work in progress. Internationalization is possible, but it demands strategy, focus and hard work.

“The future belongs to those who prepare for it today.”

Malcolm X

Question N.3 In which way the university can create strategies to prepare students for internationalization?

Internationalization is a tremendous challenge for Brazil. Brazilian High Education as a whole suffered for a long time in isolation from world academia, because of distance, language, lack of resources, and mainly the legacy of previous governments and policies. Science without Frontiers programme was a great initiative, but unfortunately was a short-lived programme.

According to British Council, 63% of Brazilian academics never had an experience abroad. Most academics have no connections beyond the 100-kilometre radius of their institution.

The case of the UK is very different – 24% of researchers at universities come from other countries. This diversity is a fundamental ingredient for the excellence of education in the country.

Internationalization intensified in the UK in the 80s. The University of Nottingham had an essential role, establishing a modern concept of “International Office”.

“International Office” is a department existent in all colleges and universities and their responsibilities include: supporting international students on enrolment and student visa enquiries, supporting current students internationalization, global marketing on behalf of the university, and coordinating cooperation with external organizations such as foreign governments and private sector. Internationalization, in order words, involves international students in the school, local students travelling for work experience or study programmes abroad, the role of foreign academics (teachers and researchers), and partnerships with public and private organizations.

Education is one of the major industries in the British economy. In the year 2014-2015, the Education sector brought a £73 billion income to the country. International students generated £25 million. HE creates around 1,000,000 jobs, and it is the third major employer in the UK.

In 2019, there were 458,490 international students in the UK, making 19.6% of the total number of university students in the country. In the same year, international academics co-authored 55.2% of academic research published in the UK.

There are 150 publicly funded universities and 14 private universities in the UK. University League Tables do not list for-profit universities, but you can find a ranked list of them here.

Besides receiving funds from the government, British universities receive income from diverse sources:

- Overseas students’ annual fees

- Home student annual fees

- Charities

- International Scholarship Programmes

- International Research funding, such as the European Research Council

- Charitable donations, trusts set up by individuals on their wills, Alumni associations contributions

- Partnerships with the industry, mostly in the R&D sector (Research and Development), for example, oil companies and Scottish universities specialized in oil studies. Students are ultimately the great beneficiaries in this case, as they prepare for the work market, having access to the most recent research and technology in the sector.

All those factors guarantee UK university’s sustainability.

The British internationalization is, above all, a result of consistent education public policies applied across several governments. Those policies and the resulting education excellence are essential to ensure the country’s development and its relevance in international geopolitics. This relatively small nation has four of the ten best universities in the world, and it is a leader in scientific research, technology, arts, among other industries.

BREXIT will represent an enormous challenge for the British Academia. The UK will lose sponsorship from European research agencies, there will also be a reduction in the numbers of European researchers and students in the UK, with the ban of free movement between the UK and European countries.

Universities are reacting and pressuring the Parliament and education authorities to keep higher education excellence and continuity in their work. One achievement is the return of the “Post-Study Work Visa”- a visa scheme that will allow graduates to work in the UK for up to two years after their graduation.

From my experience with UK internationalization, I suggest some strategies that would help Brazilian universities in their way to becoming more international institutions:

- Following what the most internationalized Brazilian universities are doing and devising strategies according to your local reality

- Using innovation to engage all stakeholders, raising funds and training towards internationalization.

- To intensify the networking with international institutions.

- Encouraging students through the publishing and promotion of opportunities – for example, the creation of a digital database, forum or a page in the History’s department webpage, listing all scholarships posts available and international research funding.

- Collaboration with the Language Departments and Faculties for future implementation of English as a working language for all researchers, like academic centres in Portugal, Italy, Poland, etc.

- The creation of better conditions, at universities, for receiving visiting lecturers and researchers.

- Working towards mutual recognition of academic qualifications

- Setting up an “Alumni Database” in the universities. This is an excellent way to follow students’ professional History, encourage networking and collaboration in relevant projects.

Still, besides the adoption of new strategies for a Brazilian internationalization, there must be a change in the mindset of many Brazilian academics regarding the quality of their academic work.

There are Brazilian scientists, researchers and lecturers developing innovative work all over the world. For example, Paulo Freire’s pedagogical approach and concepts are taught in all Education courses in the UK and worldwide, for example. Another exciting example is Ricardo Semler’s management model – research theme in all management courses in most international universities.

Between 2015-2018 there were over 13,000 papers published, co-authored by UK and Brazil researchers. 59% of these works were in the Arts and Humanities field.

There is an Association of Brazilian Postgraduate Students and Researchers in the UK, established nearly forty years ago, promoting opportunities, guiding and supporting Brazilian academics and developing closer links with several British universities.

Brazilian conservative thinking dating back to the thirties and forties and intellectuals such as Monteiro Lobato or Nina Rodrigues, underestimated national scholars compared to what was produced abroad. Those are outdated theories, and yet they surface again when some sectors of society need to justify the country’s submission to external factors and actors, lack of investment or the need for cuts in educational, scientific and cultural sectors’ budget.

As academics and intellectuals, we must react, not give up and search for opportunities using the creativity and talent characteristic of Brazil.

Question N.4: What are the challenges for history professionals, where they can use their knowledge and expertise?

Brazilians traditionally connect the historian’s profession to school and university teaching, museums and heritage sites or research in the few research centres existent.

In the United Kingdom, the knowledge of the country’s history is an integral part of the formation of the British character.

When a student search for the professional outcomes for history graduates, they find options such as

- Communications (TV, radio, journalism, documentary making)

- Defence Sector

- Finance Sector

- Civil Service

- Museums, Art Galleries and Heritage Sites Curators

- Politics

- Diplomacy

- Art (advisor for the film industry, literature, etc.)

Over the last 15 years, the UK had two history graduates as Prime Minister, from different parties: Gordon Brown and David Cameron. Prince Charles is also a history graduate.

History programmes are part of British daily life (on tv, radio and online) and they approach all ages and countries. BBC, documentaries, for example, are known worldwide.

British historians often take part in news programmes and documentaries to express their view about current affairs. For instance, there is a great debate nowadays about race and racism, including the existing historiography about British slavery and colonialism, the right to protest against racism and the fight for equality in the country. Historians are frequently leading discussions promoted by the communication vehicles and putting into context details and facts that are less known by the public.

On the selected pictures, we chose three well-known historians –

- Dame Mary Beard – classicist, professor at the University of Cambridge, published several books, art reviewer, presenter of several history-themed, art and politics programmes on tv and radio.

- Historian Ruth Goodman – as a freelance historian, she has presented several tv programmes about daily life in the UK on Tudor period, Modern History, and other subjects. She is also a consultant to writers, museums, film and tv industry.

- Historian/Professor Trisham Hunt – Professor at Queen Mary, University of London, published several books, presenter of tv and radio history programmes, politician, former Member of Parliament and current director of the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Our reference to the Black Panther movie is for the historical knowledge applied to the exquisite custom design developed for the film. There was in-depth research on textiles, clothing, symbology and culture of several African nations for the result we have seen on screen.

With these examples, we encourage students to think of the historian’s work as a vast field, not limited to classrooms.

We do not know what will happen, but we realize the world is moving towards a concept of work overriding the idea of a job.

In this new concept of work, projects, with no geographic limitations, will be the standard. An internationalized history professional will thrive. Having the tools and ability to develop work in any place, they will be ready to embrace all opportunities available.

“Start where you are.

Use what you have. Do what you can.”

(Arthur Ashe)

Readings & Resouces

These are recommendations for useful links, including scholarship sponsoring organisations and readings about internationalization (the British and the Brazilian cases). It is not a final list, but who knows a starting point to your internationalization.

- ABEP – Brazilian Association of Postgraduate Students and Researchers in the UK.

- ABEP/Brazilian Embassy in London: “The Brazilian Researchers and Students Guide in the UK”, London, 2017 (pdf format )

- Academia.edu

- Becas Santander Futuro –

- Chevening Scholarships

- Erasmus Mundus–scholarship programmes and academic opportunities for scholars, sponsored by the European Union

- Gerda Henkel Foundation – Not-for-profit German foundation offering History and Arts scholarships and sponsorship

- jobs.ac.uk (British website promoting university job positions in the UK and other countries, including PhD and Post-Doctoral research.

- thepienews.com Up-to-date news about international education

- Scholarship-positions.com– international scholarships opportunities

- scholars4dev.com/ – Extensive database with scholarship opportunities for students from developing countries

- African Union

- Universities UK – Founded in 1918, this is the representative body for 139 UK universities.

- globalscholarships.com

Other Readings

- ENGBERG, David, Gregg GLOVER, Laura E. RUMBLEY and Philip G ALTBACH: “The rationale for sponsoring students to undertake international study: an assessment of national student mobility scholarship programmes,”, London, British Council, May 2014.

http://www.britishcouncil.org/education/ihe/knowledge-centre/student-mobility/rationale-sponsoring-international-study - GÜRÜZ, Kemal, Higher Education and International Student Mobility in the Global Knowledge Economy, State of New York University Press, Albany, 2011.

- SCHWARTZ, Peter, Art of the Long View: Planning for the Future in an Uncertain World, John Wiley & Sons, New York,1997,

- SING, Navin and PAPA, Rosemary, “The Impact of Globalization in Higher Education”, International Journal of Educational Leadership, Preparation, Volume 5, Number 2 (April-June 2010), http://cnx.org/contents/4649fb69-b1a3-44c5-bcad-d9187da54236@1/The-Impacts-of-Globalization-i

- “The Wider Benefits of International Higher Education in the UK”, September 2013,BIS Research Paper 128, Department for Business Innovation & Skills. – .www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/240407/bis-13-1172-the-wider-benefits-of-international-higher-education-in-the-uk.pdf

- “The State of the Relationship UK and Brazil”:

- https://www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/International/news/Pages/the-state-of-relationship-UK-and-Brazil.aspx

- https://www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/policy-and-analysis/reports/Documents/2019/Brazil- mapping-report.pdf

- “Universidades para o Mundo: Internacionalização do Ensino Superior”, British Council’s report about internationalization and English language learning in Brazil https://www.britishcouncil.org.br/atividades/educacao/internacionalizacao/universidades-para-o-mundo

- “Why Invest in Universities?” https://www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/policy-and-analysis/reports/Documents/2015/why-invest-in-universities.pdf